🎄 Ancient Beat #177: Huge undersea walls, new hominins, and the Indus Valley collapse

Hello, friends! Happy Friday and Happy Holidays!!

If you’re a last-minute shopper, here’s an easy gift idea — give them the Beat! 🕺

Not like dropping a beat (though that might be an even better idea). Ancient Beat — the gift that keeps giving every week. Buy a subscription as a gift here.

Speaking of gifts, there’s a little treat for free subscribers below.

Annnnd, here’s the latest ancient news. 👇

🗞 Ancient News: Top 5

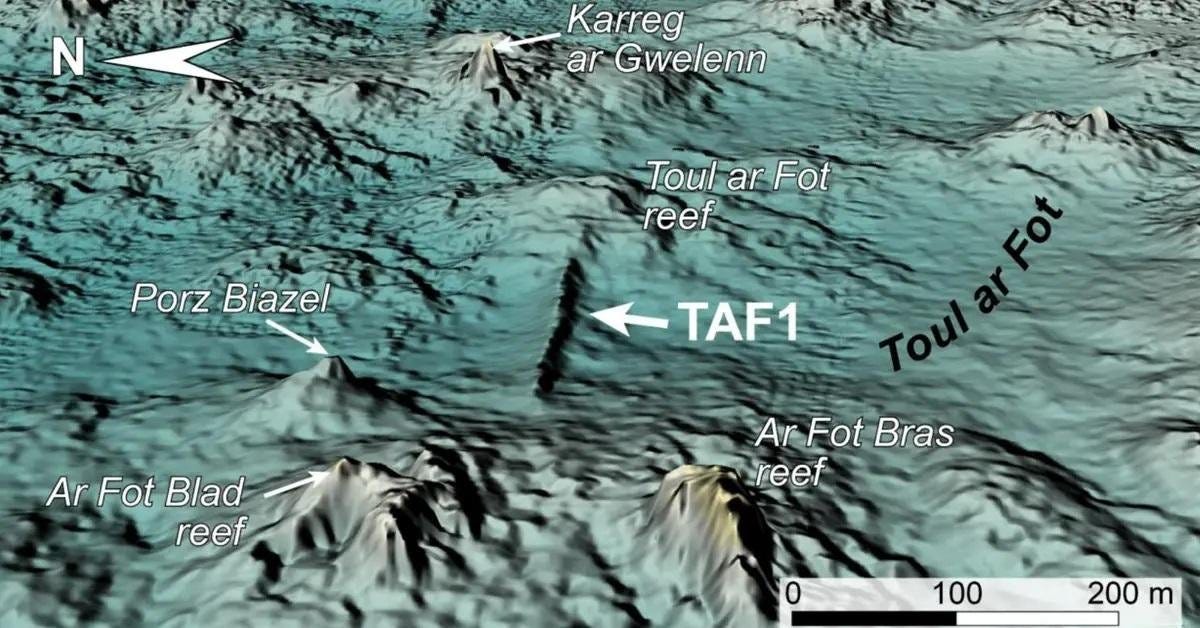

Huge Ancient Undersea Wall Dating to 5800 BCE Discovered Off the French Coast — Here’s a wild one. It was first noticed a few years back, but a paper just got published. Off the coast of Brittany, France, near Île de Sein, divers have documented a vast submerged stone complex dating to roughly 5800–5300 BCE during the Late Mesolithic–Early Neolithic transition, when sea levels were lower. The largest feature is a 120 m (≈394 ft) long granite wall, flanked by 60+ upright monoliths and slabs reaching nearly 2 m (~6 ft) in height, uncovered through underwater surveys and LIDAR mapping. At least a dozen additional structures cluster nearby, some resembling smaller walls and lines of stones that may have acted as fish traps or barriers in the then-coastal landscape. The scale and craftsmanship imply complex planning, quarrying, transport, and coordinated labor among prehistoric coastal communities centuries before the region’s first known megalithic monuments. Rising seas would later submerge the site, preserving it under roughly 7–9 m (~23–30 ft) of water and offering new windows into early engineering and shoreline occupation.

Little Foot Hominin Fossil May Be New Species of Human Ancestor — The famous Little Foot skeleton from South Africa’s Sterkfontein caves — one of the most complete early hominin fossils known, with an age estimate between roughly 3.7 and 2.8 million years ago — may not belong to any species previously assigned. New analyses of its skull anatomy, especially the base of the cranium, find significant differences from both Australopithecus africanus and the contested A. prometheus, suggesting it represents a distinct lineage of early human ancestor. If confirmed, this could add an entirely new branch to the hominin family tree, complicating what was already a rich picture of early human diversity in southern Africa and underscoring the mosaic nature of our evolutionary history.

Scientists Finally Uncovered Why the Indus Valley Civilization Collapsed — New climate reconstructions show that the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization, which flourished from about 3000 BCE to 1500 BCE along the Indus River in today’s Pakistan and northwest India, was driven by repeated, long-lasting droughts rather than a single catastrophic event. A series of dry periods, each lasting more than 85 years, gradually reduced rainfall and pushed communities closer to reliable water sources. One especially extended drought from about 1531 BCE to 1418 BCE aligns with archaeological evidence for widespread deurbanization and shrinking settlements. Earlier in its history (4500–3900 years ago), the civilization sustained planned cities with advanced water management, but as rainfall patterns shifted, populations dispersed and urban complexity waned. This view reframes the “collapse” as a protracted transformation shaped by environmental stress.

Terra Amata Site Reveals Technological Flexibility of First Humans in Europe — At Terra Amata on the French Riviera, early humans occupied a marshy delta environment about 400,000 years ago, transporting raw materials up to ~25 mi (40 km) and repeatedly returning to the site. A new study of limestone tool debris shows local cobbles were shaped with simple knapping but also include early evidence of structured flaking, platform preparation, and organized cores—innovations that foreshadow later Levallois techniques. These patterns point to adaptable tool strategies, territorial mobility, and nuanced resource use among early hominins in a diverse Middle Pleistocene landscape.

With Feathers Into the Afterlife: New Results on the Bad Dürrenberg Shaman Burial — A Mesolithic burial dating to about 9,000 years ago at Bad Dürrenberg in central Germany reveals new evidence of feather ornamentation likely tied to ceremonial attire. Microscopic fragments of goose, songbird, and grouse feathers were found in the head region of a woman buried holding a 6-month-old infant, supporting earlier reconstructions of an elaborate feathered headdress and reinforcing interpretations of her as a shaman or spiritual specialist. The original 1934 discovery—which had to be rescued quickly during construction—left much of the burial pit undisturbed; recent excavation and lab analysis have recovered previously overlooked materials. A nearby pit, placed about 600 years later, contained two deer-antler masks with traces of feathers and bast fibers, suggesting ritual offerings long after her death. These delicate feather remains, rarely preserved in soil, provide rare direct evidence of prehistoric adornment and symbolic practice in Central Europe’s early hunter-gatherer communities. I’ve covered this burial before and it always amazes me. Can you believe people were leaving offerings 600 years later?! What a story this person must have had.

🎁 In the holiday spirit, no paywall here. Carry on.

🗞 Ancient News: Deep Dive

Rare Discovery: Menorah Amulet From Byzantine Period Found in Jerusalem — Right in time for Hanukkah, a small lead pendant decorated on both sides with a seven-branched flaming menorah was uncovered in Jerusalem, near the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount, within a Late Byzantine–period building buried beneath about 26 ft (8 m) of debris. The object dates to roughly 1,300 years ago (6th–early 7th century CE), a period when Jews were officially banned from living in the city. The pendant is circular, crudely cast, and made of ~99% lead, the cheapest and most accessible metal of the time, commonly used for pipes, construction, and amulets. One side is well preserved while the other is patinated, suggesting prolonged wear. Its lack of ornamentation and fragile material indicate it was likely worn discreetly as a protective amulet, possibly beneath clothing, rather than displayed as jewelry. The find supports historical and archaeological evidence that Jewish visitors or traders continued to access Jerusalem sporadically despite formal prohibitions. This is only the second known lead menorah amulet ever identified, making it an exceptionally rare artifact of personal devotion and identity in Late Antiquity.

A Hidden Climate Shift May Have Sparked Epic Pacific Voyages 1,000 Years Ago — Around 1000 CE, a major shift in rainfall patterns across the South Pacific may have helped fuel the last great wave of Polynesian eastward expansion. High-resolution records of ancient plant waxes preserved in island sediment show drying trends in western island groups like Samoa and Tonga, while eastern islands such as Tahiti became wetter and offered more dependable freshwater and agricultural potential. This “chasing the rain” dynamic likely created both push and pull factors: diminishing rainfall making life harder in the west and enhanced water availability making eastern islands attractive for settlement. Climate model simulations link these changes to an eastward shift in the South Pacific Convergence Zone between about 1100 and 400 years ago, aligning with archaeological evidence for sustained human voyaging and colonization across vast stretches of ocean.

6,000-Year-Old Skeleton Reveals Survival After a Violent Lion Attack — In a Copper Age (fifth millennium BCE) necropolis near Kozareva Mogila, Bulgaria, researchers uncovered the remains of a tall young male who survived a severe lion assault long enough for notable healing to occur. The skeleton bears multiple crushing and puncture wounds to the skull — including a large breach into the cranial cavity — as well as injuries to the legs, shoulder, and arm consistent with powerful carnivore bites. Evidence of bone remodeling shows he lived for weeks or months after the attack, implying substantial care from others in his community despite likely permanent disability. He was buried in a deep grave in a crouched position without goods, suggesting altered social status after his injuries. This rare bioarchaeological case paints a vivid picture of human-wildlife confrontation, prehistoric medical care, and social dynamics among Eneolithic groups on the Black Sea’s edge.

Stories From Traditional Knowledge Combined With Archaeological Work Trace 2,300 km of Songlines — In Australia, researchers are linking First Nations oral traditions — Songlines that record journeys, rituals, and place names — with archaeological evidence to map ancient cultural routes spanning roughly 2,300 km across the continent. These Dreaming tracks connect ceremonial sites, water sources, and landmarks, embedding landscape knowledge in ritual song and story. Where past violence and disruption obscured archaeological signatures, traditional narratives help pinpoint locations and interpret material finds, reinforcing the deep time continuity of Indigenous knowledge systems across vast distances and millennia.

Stone Age Dog Burial Unearthed in Swedish Bog — In southern Sweden near Järna, archaeologists uncovered a rare Stone Age burial of a large male dog dating to roughly 3000 BCE. The nearly complete skeleton stood about 20 in (52 cm) tall and was found intentionally interred in wetland sediment alongside a finely crafted bone dagger about 10 in (25 cm) long made from elk or red deer bone. The dog’s skull was crushed, and evidence suggests it was placed in a leather container weighted with stones to sink it into what was once a lake used for fishing. Wooden pilings, ancient pier remains, and fishing tools at the site point to past economic activities. The careful burial with a weapon implies a ceremonial or ritual context, as intentional dog deposits are known from other Stone Age wetland sites in Scandinavia. Plans for radiocarbon and DNA analysis aim to refine dating and shed light on the animal’s life history and its human companions.

Study Is Unlocking Secrets Of Roman Empire’s Leather Economy — New research is applying advanced scientific techniques, including ancient DNA sequencing and biomolecular analysis, to leather artifacts from Roman sites across Europe and the Near East to better understand leather production, trade, and use across the Roman Empire. Well-preserved leather from locations such as a fort near Hadrian’s Wall in Britain, and sites in the Netherlands and Syria forms the core of this material. Leather objects — from everyday wear to military gear — normally survive poorly in the archaeological record, so this project aims to reconstruct ancient manufacturing processes, supply networks, and economic roles of leatherworking in provincial and metropolitan contexts. Integrating these data with other lines of evidence promises fresh insight into how this durable material supported military logistics, craft traditions, and long-distance exchange within the empire’s vast economy.

16th-Century Gallows Excavated in France — Excavations in Grenoble, southeastern France, uncovered the remains of a sixteenth-century gallows and associated burial pits tied to the town’s official execution site. The gallows structure measured about 27 ft long with stone pillars over 16 ft tall supporting timber crossbeams where up to eight condemned individuals might have been executed and their bodies displayed. Archaeologists uncovered 32 skeletons in nearby pits, most male and several showing evidence of decapitation or dismemberment consistent with violent death or post-execution treatment. The gallows were in use until the early seventeenth century, offering a rare window into late medieval to early modern punitive practices, public execution spaces, and burial of executed individuals in urban contexts.

Beachy Head Woman’s Origin Story: DNA Analysis Reveals She Was Local to Southern Britain — A Roman-era individual unearthed near Beachy Head in southern England, long debated for her origins, was confirmed by ancient DNA sequencing to have been local to Britain rather than from sub-Saharan Africa or the Mediterranean. Her remains date to the Roman occupation period (roughly 2nd–3rd century CE), and earlier morphological and partial genetic studies had led to conflicting hypotheses. High-quality DNA now shows she fits within the genetic variation of southern British populations of her time, overturning earlier assumptions about long-distance migration for this individual and highlighting how advancing genetic methods can refine bioarchaeological interpretations.

Ancient Hunter-Gatherer DNA May Explain Longevity in Some People — Genetic comparisons between modern Italian centenarians and ancient genomes reveal that people who live to 100 years or more tend to carry higher proportions of DNA from Western Hunter-Gatherer populations that lived in Europe after the last Ice Age. In a study comparing genomes of 333 centenarians and 690 adults in their 50s with 103 ancient genomes, only Western Hunter-Gatherer ancestry correlated with longevity. Each incremental increase in this ancestral component raised the odds of reaching 100 by about 38 %, especially in women. Scientists suggest these ancient genetic variants—selected for survival in harsh Ice Age conditions with limited food—might enhance metabolism and immune resilience, offering a potential inherited boost to long life.

Bronze Age DNA From Calabria Reveals a Distinct Mountain Community — Ancient DNA from human remains at Grotta della Monaca in the Pollino massif of Calabria, southern Italy, dated between about 1780 BCE and 1380 BCE, paints a picture of a Middle Bronze Age mountain community with deep regional roots. Genetic analysis shows this group’s ancestry connects strongly with Early Bronze Age Sicilian populations, with additional inputs from northeastern Italy and mixed hunter-gatherer, early farming, and Steppe ancestries typical of Bronze Age Europe. The cave served as a collective burial place, suggesting strong family and community ties. This genetic and archaeological snapshot highlights mobility patterns and social structure in a Mediterranean highland society amid broader Bronze Age interactions.

8.2 ka Event Triggered Social Transformation, Not Destruction, at China’s Jiahu Site — Evidence from the Jiahu archaeological site on China’s North China Plain (occupied between 9.5 and 7.5 ka BP) suggests that the abrupt 8.2 ka climate event did not cause societal collapse there but instead spurred significant social reorganization. This short-lived global climatic downturn, marked by cooling and drying, is often seen as catastrophic. At Jiahu, burial numbers surged during the event phase, indicating increased mortality and possible immigration, and the community adapted by redistributing labor and strengthening cooperation in resource management. After conditions eased, burial numbers declined and grave goods became less common, underscoring active reconfiguration rather than simple decline. These patterns illustrate early human capacity for resilience and adaptation to abrupt climate shifts rather than uniform social devastation.

New Biomolecular Technique Uncovers Millet in Medieval Ukrainian Dental Calculus — A cutting-edge chemical method (thermal desorption gas chromatography–mass spectrometry) detected trace molecules from broomcorn millet preserved in dental calculus from people buried at the Ostriv cemetery in central Ukraine dating to the 10th–12th centuries CE. This is the first time molecular evidence of millet consumption has been found directly in human plaque, revealing that individuals ate this C4 crop even when conventional isotope tests failed to register it. Eight of 31 individuals showed the millet biomarker, suggesting occasional or later-life dietary shifts, possibly linked to migration or changing food availability. The technique works on tiny samples and could transform how archaeologists trace underrepresented plants in ancient diets across the world.

Bayeux Tapestry Could Have Been Originally Designed as Mealtime Reading for Medieval Monks — A fresh interpretation suggests the nearly 224 ft (68 m) Bayeux Tapestry, which narrates the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, may have been intended for display in the refectory (communal dining hall) of a medieval monastery such as St Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury. In this setting, monks could view the embroidered scenes and Latin captions at close range during meals, possibly alongside oral readings, blending visual narrative with moral instruction. There’s no direct record of the tapestry’s early display before it appears in a 1476 inventory at Bayeux Cathedral, but the refectory theory helps explain how such a long, detailed work might have been viewed and interpreted in everyday monastic life.

How Water and Clay Shape the Archaeological Record at Murujuga — Research in the clay-rich soils of the Murujuga Cultural Landscape in Western Australia shows that swelling and shrinking from wetting-drying cycles can slowly push stone artifacts upward toward the surface over time. This natural soil movement can mix materials from different periods and create surface concentrations that don’t reflect original human deposition, complicating interpretations of artifact distributions. The work highlights the need to integrate soil science and geomorphology with archaeological methods—especially in clay-dominated landscapes like this World Heritage-listed rock art region—to avoid misleading conclusions about past human activity.

Stagnation or Strategy? The 5,000-Year Standstill of a Rainforest Toolkit — Excavations in Pahon Cave, Gabon, preserve an unusual record of human activity in Central African rainforest contexts. Over 5,000 years (Holocene), inhabitants repeatedly made and used stone tools of remarkably similar form, showing little technological change despite environmental shifts and broader regional transformations. Rather than stagnating, this long-term consistency may reflect a strategic optimization of a toolkit that reliably met daily needs in dense tropical forest — hunter-gatherer ingenuity embedded in ecological stability rather than chasing innovation for its own sake.

When Bones Remember Ligaments: Reading Ancient Movement in the Wrist — Movement isn’t written only in bone shape — the sites where ligaments once attached also hold clues. By applying 3D geometric morphometrics to the wrist bones of fossil radii, researchers can infer how joints behaved under movement stresses, offering fresh insight into how early hominins balanced climbing, walking, and manipulation. This ligament-informed approach adds a new dimension to debates about locomotion and hand use in human evolution.

The Face That Refuses to Fit: Rethinking the Rise of Homo erectus — A newly reconstructed early human skull from Gona, Ethiopia, dated to roughly 1.5 million years ago, is complicating long-standing ideas about the emergence of Homo erectus. Known as DAN5, the fossil presents a striking anatomical mix: its braincase aligns with classic Homo erectus expectations, while its face and teeth retain traits more typical of earlier Homo forms. This mosaic challenges the textbook view of Homo erectus as a neatly defined, stable package of traits that appeared suddenly and then spread across Africa and Eurasia. Instead, the evidence suggests a gradual, uneven transition, with different parts of the skull evolving at different rates. The find raises questions about how early human populations were structured, how traits spread through migration, and whether Homo erectus represents a single coherent species or a broader, evolving lineage during the early Pleistocene.

How Did the Roman Invasion of Britain Impact Health? — Skeletal evidence from south and central England shows that the Roman occupation, beginning in 43 CE, coincided with a measurable decline in health among women and infants, particularly in urban settlements. Analysis of age at death and pathological markers such as skeletal lesions indicates worsening overall health during the Roman period compared with pre-Roman communities. The impact was uneven: people living in towns and cities experienced the most severe decline, while those in rural areas showed only a slight increase in disease exposure that was not statistically significant. Urban health stress is linked to overcrowding, pollution, reduced access to resources, and especially lead exposure associated with Roman infrastructure, including pipes and construction materials. The findings highlight how urbanization introduced by Roman rule reshaped daily living conditions, with health burdens passed from mothers to children, leaving long-term biological traces in the population during Britain’s transition into the Roman world.

❤️ Recommended Content

Here’s an article about the need for imagination in archaeology.

Here’s an article unpacking the baggage of the word “culture.”

If you’d like to learn about an 18th-century Maori war cloak, here’s an article about one being returned to New Zealand.

Here’s a thread about the likelihood of a future archaeologist finding something of yours.

Here’s an article about finds within the Great Wall of China.

Here’s an article about Denmark’s oldest plank boat.

Here are seven of the most fascinating archaeological finds of 2025.

And here are Scotland’s top finds of 2025.

There you have it.

There won’t be another Ancient Beat until the new year. I know, I know. What will you ever do without it? Take heart, friends: We’re sure to have lots of juicy tidbits to discuss when we’re back.

Have a wonderful holiday season!

-James

P.S. Here’s my Buy Me A Coffee link if you’d like to support my efforts with a donation.

🧐

Stellar roundup. That undersea wall off Brittany is wild becuase it predates the region's known megalithic monuments but already shows organized labor and quarrying at scale. I remember reading about submerged coastal sites and how much prehistory is probably buried offshore, but seeing coordinated enginering this early really shifts timelines. The Indus Vallley collapse framing as gradual transformation rather than sudden catastrophe is a much better model too.